Ballet Lessons on the Berlin Wall

Setting: a shabby American Legion Hall in the NYC suburbs, circa 1976

Action: As the curtain rises, 57-year-old Henia Stankiewicz, an arthritic prima ballerina from Poland, removes her portable record player from the closet and plugs it in. Placing the needle on a scratchy, vinyl LP, she closes her eyes as the first few notes from Chopin’s “Grande Valse Brillante” fill the air. “Who wrote this music?” she asks her young pupils.

It’s another day in paradise – IF you’re a leggy little 9-year-old in fresh pink tights. A new class at Madame Henia’s School of Classical Ballet (“Specializing in Vaganova Technique”) is about to begin…

Although I never really mastered Vaganova technique (or any other ballet methodology, for that matter), twenty years of intensive dance training certainly taught me priceless lessons about focus, discipline and humility. Thanks to a series of gifted instructors, my ballet education touched upon everything from human anatomy and nutrition to anthropology, French history, Russian literature, and even epidemiology (see AIDS Crisis, 1981). All throughout childhood, dance was the primary lens through which I explored and understood the world around me.

This week, as the West prepares to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the Berlin Wall’s demise, I am remembering my beloved teacher Madame Henia, and her courageous flight to freedom. During the height of the Cold War, at a time when the defections of ballet superstars like Rudolf Nureyev (1961), Natalia Makarova (1970) and Mikhail Baryshnikov (1974) grabbed international news headlines, lesser known asylees like Madame struggled to survive on the margins of western society.

To my 9-year-old eyes, Madame seemed like some sort of deposed queen. Despite the indignities of arthritis and a disappearing waistline, she always draped herself in a cloak of elegance that was indestructible – even when challenged by forces as powerful as communism, poverty and exile.

She was obsessed with maintaining good posture – mine, her own, and everybody else’s as well.

One year at Christmastime, I innocently asked Madame if she was going “home” for the holidays. Suddenly, my authoritarian-but-always-loving mentor, whom I adored like a third parent, completely lost her composure. One breath later, she was literally heaving with sobs…, and somehow I was to blame. Unable to grasp how I had harmed this exotic, invincible lady, I simply burst into tears as well. She hugged me and we cried together for a very long time.

Later that evening I begged my mother to explain how my question about Christmas could have wounded Madame so deeply. “She misses her family,” my mother explained, “and she can never return to her homeland because there’s an iron curtain across Europe.”

An iron curtain?

The only “iron curtain” I had ever seen was firmly attached to a fireplace…, where its purpose was to prevent sparks from flying onto the carpet.

For the next several years, I wondered why anybody would want to cordon off an entire country behind a giant expanse of chainmail. I figured that Poland was suffering from an awful lot of forest fires.

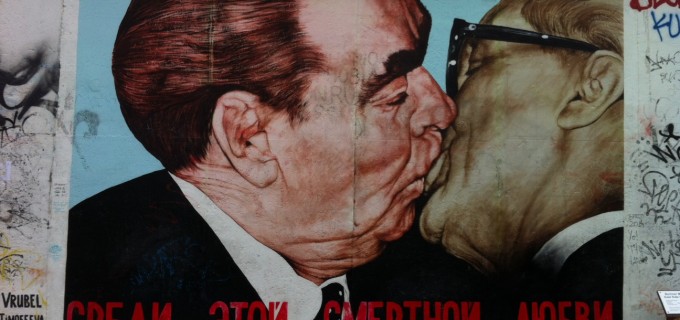

Zoom forward to 1979, to the moment when Bolshoi virtuoso Alexander Godunov sought political asylum at JFK Airport. Godunov’s high-stakes standoff with the KGB attracted personal involvement from the Cold War‘s two leading titans: US President Jimmy Carter and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev. [From the very beginning, Godunov’s defection read like a chapter from a spy novel, so it came as no surprise when his story inspired a 1986 film called Flight 222.].

Immediately after winning asylum, Godunov joined Baryshnikov and Makarova at American Ballet Theatre. Although I was still in middle school and didn’t yet have a passport, the years I spent under Madame Henia’s tutelage made fallout from foreign policy feel very real, and deeply human. I was beginning to understand terms like “Eastern Bloc,” “amnesty” and “human rights.” Although neither of us realized it at the time, Madame had already ignited my lifelong passion for international relations and cultural diplomacy.

On November 9, the “fall of the wall” will be celebrated around the world with plenty of currywurst, beer and fireworks. Tele-historians will reflect upon those who risked their lives at Checkpoint Charlie. Memorial wreaths will be laid for the escapees who died there.

I look forward to attending a party hosted by my dear friends Stef and Olli, who were both born under dictatorship in the former East Germany. At some point during the festivities, I will share the story of an obscure, Cold War era ballerina whose influence turned me into a global citizen.

And as the evening draws to a close, maybe we will all listen to Chopin.